As evening falls on Cambridge, writer and veteran campaigner Harry Leslie Smith eases himself into a chair and, after a long day travelling, sips a coffee and enjoys a welcome bite of apple crumble.

At 92, such journeys take longer to get over, so he’s arrived in the city early so that he can be fully rested when he’s due to speak at a meeting the following night.

Just a couple of days before, he’d been in the north east, addressing a protest by junior doctors over the government’s plans to enforce new contracts on them.

Not for the first time, Harry brought tears to the eyes of his audience with his memories of the dreadful privations of the Depression of the 1930s.

Yet he also found himself bemused by a stream of shoppers scurrying in and out of a shopping arcade, barely paying attention to the protest, as though the problems facing the NHS had nothing to do with them.

Harry’s memories include hearing the screams of a dying woman whose family could not afford painkillers, and his own sister’s death of tuberculosis in a workhouse after their parents could no longer care for her.

And now, the knowledge that such diseases are making a comeback as poverty rises adds an added piquancy to what Harry himself has to say.

How, he muses, have we reached a point where people care more about shopping than our collective well being?

Love among the ruins

This punishing tour of Britain is partly to promote his new book, Love Among The Ruins: A Memoir of Life and Love in Hamburg, 1945.

In that book, he talks of how, as an RAF man stationed in the north German city at the end of the war, he met and fell in love with his wife, Frieda.

Their ‘fraternising’ was met with hostility on both sides.

Harry notes that wanting to be with “a foreign girl” was so bad that “you were forbidden to walk in the street together.” When they were courting, his future wife “would have to walk several steps ahead of me, otherwise I would have been taken in and challenged”.

He and Frieda were made to jump through many hoops in order to be together, with his military bosses treating them with real nastiness.

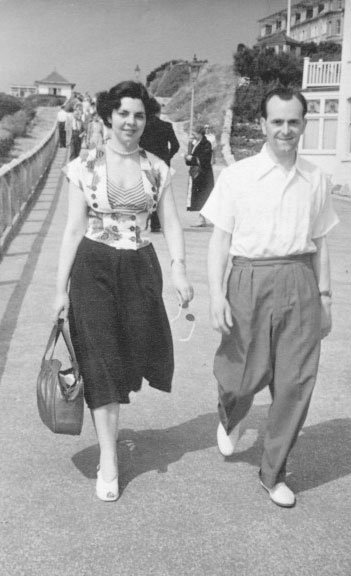

Yet he notes that when they were back in England (pictured below), most people soon got accustomed to the marriage when they saw that Frieda was no different to any of them.

“It was unbelievably tough in those years after the war,” he notes. “I didn’t come back until ’48. You couldn’t find a place to live. We lived in one room. If she [Frieda] wanted to do washing, she had to do it in the bathtub down the hall.”

He pauses for a few moments.

“At that time, of course, England was run by people who owned mills and mines, and they decided what the poorer people of England were going to get.”

This is not, though, an idle contemplation of the past.

“It’s going back to how it was when I was a young boy,” he says. “There is no justice for ordinary people; there’s no life; there’s no hope.”

Rarely in life do we encounter another person who has watched as almost a century has passed. Meeting Harry is to experience history concertinaing in front of you.

In 1926, the year of the General Strike, Harry rode on the shoulders of his father – a Yorkshire miner – to a union meeting.

And he still remembers his family being kept from starvation by the union. It’s one of the reasons that he believes unions are absolutely vital for working people.

“I never dreamed I’d see these food banks and zero-hours contract jobs – and young people who have no hope any more,” he says. “They can’t dream, as we dreamed. They can’t say: ‘Things are going well, maybe in another five or six years we’ll be able to buy a little house of our own’. They’re lucky if they can buy a one-roomed apartment.”

‘We’re here to make a difference’

But with all this in mind, what makes him carry on? If that’s the way it is, what’s the point?

“Maybe – just maybe – by my voice going around, I can make people realise that the answer is with the people. It is they who will decide who is going to rule this country.”

Harry longs to see someone who will do more than simply “fill the coffers of the 1%,” he says.

“I’m just an ordinary man, and it boggles my mind that people have a million, they have a billion and they’re not satisfied. What can they do with it?”

Frieda died in 1999 and Harry has said that “being online has made my life less lonely.” At the same time, social media has given him another platform for his campaigining.

“It’s only hope that drives me on to do my utmost. We have to feel that we can make a difference in this world – that we’re here to make a difference. If we put our shoulders to the wheel and get ourselves out of this rut we seem to be in, I think we could change this country for the better.

“I still feel that there’s too many people who feel there’s nothing they can do to change things – that because they think that, they just won’t get up off their arses and put some skin in their game, you know.”

Harry is a remarkable man – and long may he continue to chivvy us into remembering that it’s not a waste of time to fight to make ours a better world.

You can follow Harry on Twitter at @Harryslaststand.

Love Among The Ruins: A Memoir of Life and Love in Hamburg, 1945 is out now, published by Icon Books.